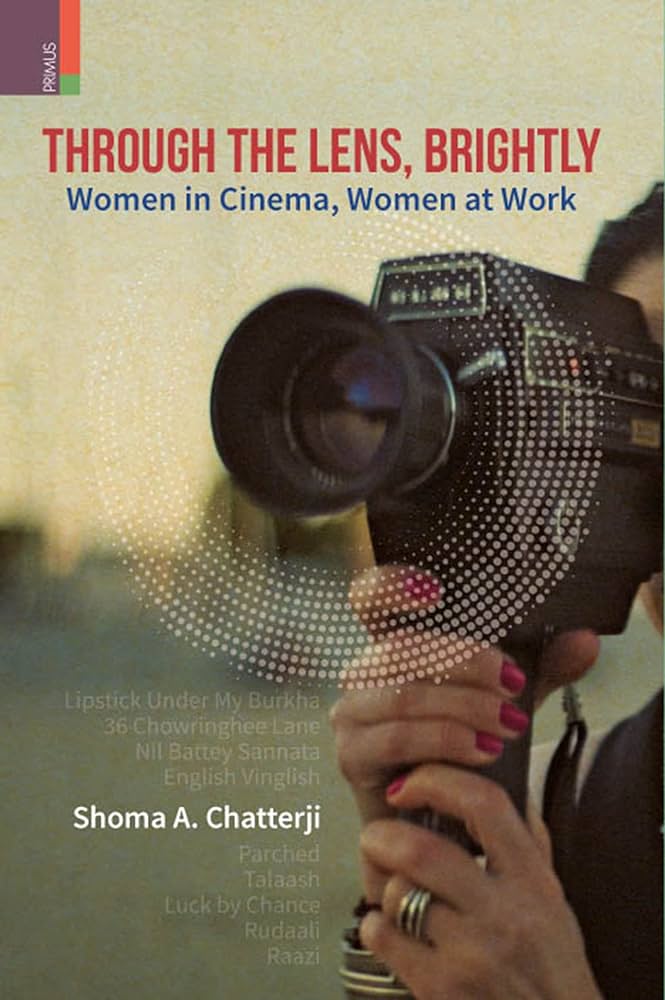

Through the Lens, Brightly: Women in Cinema, Women at Work is National Award- winning writer Shoma A. Chatterji’s latest offering on women behind the lens. The contents page of the book can be a wee bit misleading because at first glance you might feel the writer has picked up films that we have already watched and re-watched, by women directors we are largely familiar with. But when it’s a book by Chatterji, you can expect the unexpected. What could have been a run-of-the-mill discourse has turned out to be an eye opener. It’s a highly entertaining and inspiring read. Peppered with interesting anecdotes, unknown facts and the author’s personal views, the book very intelligently steers clear from becoming an academic read. At the same time, it is a gem in the hands of students and researchers doing women’s studies, aspiring filmmakers, film scholars and students of film studies.

At the beginning of the book, Chatterji points out that women were mostly part of the film industry the world over because they brought the glamour quotient to the screen and having the acting chops wasn’t a necessity. Post WWI Hollywood saw the emergence of Dorothy Arzner, the first woman who wore the director’s cap. At almost the same time, India was also witnessing a similar change.

The first women directors in India

The book takes off from the fascinating perspective of how the first few Indian women took up their place behind the camera, making an unusual career choice in a male-dominated profession and making their presence felt.

As Chatterji writes, the history of Indian women directing films dates back to the silent era. Way back in 1926, it was Fatma Begum who started her own company Fatma Films and made six films; some of the popular ones being Bulbul-E-Paristan, which first treaded the world of fantasy, Heer Ranjha and Shakuntala. She belonged to Urdu theatre and had worked with noted filmmakers Ardeshir Irani and Nanubhai Desai. Her daughter actress Zubeida was the heroine of the first talkie Alam Ara.

If Fatma paved the way for women to step behind the camera, superstar Nargis’ mom Jaddanbai was another ambitious lady who started the Sangeet Film Company in 1936 and directed films like Hridaya Manthan and Madam Fashion. In fact, at the age of six, Nargis made her acting debut in the film Talash-e- Haq where Jaddanbai was the heroine. Chatterji has added details about the fascinating life of Jaddanbai, the social scenario in the film industry at that time as it evolved into a respectable profession for women and how Jaddanbai, the grandmother of Sanjay Dutt, understood the opportunities the film industry in Bombay offered even in its nascent state and built on it using her prowess in acting, music and directing.

Jaddanbai, the grandmother of Sanjay Dutt, understood the opportunities the film industry in Bombay offered even in its nascent state and built on it using her prowess in acting, music and directing.

Shobhna Samarth started her career as an actress in Marathi films but she went into direction and production and eventually launched daughter Nutan as the lead in her directorial Hamari Beti and Tanuja in Chhabili.

In Bengal, noted actress Arundhati Devi received the Certificate of Merit at the National Awards in 1967 for her film Chhuti where, apart from direction, she had done the script and music. She also directed the children’s film Padi Pishir Bormi Baksha and produced Bicharak in 1959 that has stunning performances by her and Uttam Kumar.

Actress Manju De made her directorial debut with the comedy Swargo Hotey Biday in 1954 and then she directed the hugely popular Byomkesh story Sajarur Kanta (1974) which was a runaway hit.

South Indian actresses Bhanumathi, Lakshmi, Kommareddy Savitri also tried their hands at direction and succeeded.

The change in the narrative

These early women directors had undertaken an uphill task in a male-dominated industry where the storytelling, distribution, pumping in the moolah into films, were all perceived from a man’s perspective. That’s why the heroine on screen had to be either the victim or the good girl, or the vamp placed solely for voyeuristic pleasure, bestowed with all vices. Films were made in formulas that worked again and again so the trap was inescapable.

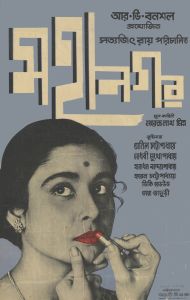

It was men like Satyajit Ray with his focus on a working woman in Mahanagar, Vijay Anand with Rosie’s atypical character of wife, lover, dancer in Guide or Guru Dutt through Chhoti Bahu’s character in Sahib, Biwi Aur Ghulam, challenged stereotypes. But interestingly, when women started directing films in India, it wasn’t with a hunger to challenge stereotypes but the perspective that they brought to the silver screen was fresh and different. From delving into fantasy to children’s films to detective stories to social drama, they told their stories in a different way and almost always, the objectification of women, that was so far the norm, was totally missing.

It was men like Satyajit Ray with his focus on a working woman in Mahanagar, Vijay Anand with Rosie’s atypical character of wife, lover, dancer in Guide or Guru Dutt through Chhoti Bahu’s character in Sahib, Biwi Aur Ghulam, challenged stereotypes.

Women directors of the 80s

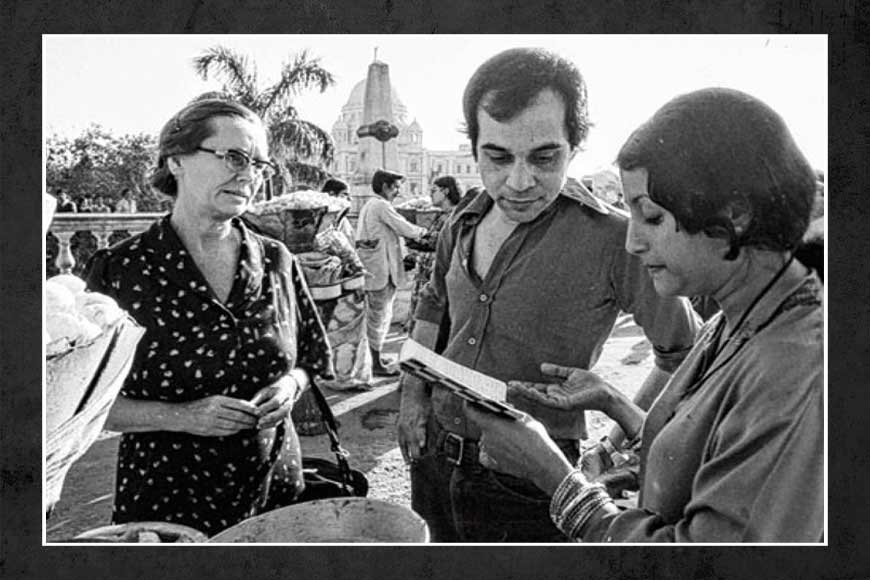

If we are talking of emergence of women directors in the 80s, as Chatterjee rightly points out, we cannot help but take off with Aparna Sen and her path-breaking film 36 Chowringhee Lane. The actress, by stepping behind the camera and by staying behind it for four decades, has been an inspiration to many women.

While later in the book Chatterji takes a nuanced look at Aparna Sen’s debut film that was initially a dud at the box office and later attained cult status, redefining storytelling in Indian cinema, in the initial part the author talks about women directors who made their presence felt in the 80s.

She touches upon Kalpana Lajmi, the niece of Guru Dutt and cousin of Shyam Benegal, who started directing her own films after working with her cousin for 10 years. Other noted directors she talks about are Vijaya Mehta, who was a well-known theatre personality and Sai Paranjpayee who became a household name with her film Chashme Baddoor. Chatterji has detailed their work, their successes, failures and the direction they gave to Indian cinema.

Women moving forward behind the lens

Chatterji mentions that the only thing that was common among the women directors of the 80s was the fact that they bonded through strong storylines, were versatile and had a fresh voice and their films had beautiful music.

As the writer shares interesting anecdotes about each lady director, about their ambitions and struggles, we move into the 90s when we have women who are more focused and sorted. She mentions Odiya director Bijoya Jena whose directorial debut Tara (1992) got the National Award for the Best Odiya Film. Some other noteworthy names are Gopi Desai, Prema Karanth, Satarupa Sanyal, Sumitra Bhave and Aruna Raje whose latest film Firebrand was produced by Priyanka Chopra for OTT.

And then there were the “others” like Mira Nair, Deepa Mehta, Gurinder Chadha and Pamela Rooks. They are considered the “outsiders” because they did not supposedly belong to Indian film industry and their crew comprised technicians from East and West, but the author points out that they are as much part of this milieu because they have gone ahead and challenged stereotypes and told very strong Indian stories. Mehta’s Fire, Nair’s Namesake, Chadha’s Bend It Like Beckham haveattained cult status.

Coming to the present

Among the present crop of women directors, the author mentions Reema Kagti who made her debut with the refreshing Honeymoon Travels Pvt Ltd, Meghna Gulzar’s films Raazi and Talvar, Leena Yadav’s Parched, and Zoya Akhtar and Farah Khan, both of whom have stuck to mainstream films and neither makes feminist films nor off-beat ones. Nandita Das’ Manto, Konkona Sen Sharma’s Death in the Gunj and Kiran Rao’s Dhobi Ghat are a few films that the author mentions as commendable productions.

In a very interesting section “Ladies Behind the Scenes”, Chatterji elucidates that a study in Hollywood has shown that women in crew positions only formed 22.6 % of people behind the camera. The story in India is no different, although it’s changing gradually.

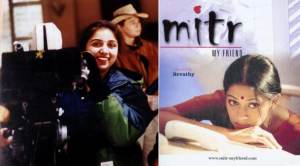

Way back in 2002, Revathi’s film Mitr, My Friend had an all-women crew and it clinched a number of awards at the National Awards. Anu Menon’s 2015 film Waiting also had an all-women crew as did Priya Beliappa’s Kannada film Ring Road in 2014. The author has given more instances in the book saying it’s rare, but it’s happening.

Way back in 2002, Revathi’s film Mitr, My Friend had an all-women crew

The films in focus

In this book, Chatterji has mainly focused on how working women have been depicted in films made by women. In Aparna Sen’s 36 Chowringhee Lane, Violet Stoneham is a teacher, in Kalpana Lajmi’s Rudaali, the protagonist tries to be a part of a fading profession of lamenting women, in Leena Yadav’s Parched, the characters are crafts women and there is a travelling dancer who moonlights as a sex worker, Gauri Shinde’s English Vinglish focuses on the entrepreneur, Zoya Akhtar’s Luck By Chance has the actress as a working woman, Reema Kagti’s Talaash is about a sex worker, Ashwini Iyer Tiwari’s Nil Battey Sannata has a multi-tasking domestic maid, Alankrita Shrivastava’s Lipstick Under My Burkha covers roles like a landlady, a beauty salon worker and a nude model and Meghna Gulzar’s Raazi looks at the working woman as a secret agent.

Chatterji, through her research, has delved into the life of the working women, their images represented by the directors on celluloid and the changes their occupation brought to their lives.

Till date, there has been very little work on representation of working women in Indian cinema and one must say as one goes through the pages of the book one is amazed at the kind of research the author has done not only on each film but also on each director. The details about a director’s background, their struggles and how they wanted to get their POV across make for a truly enthralling read.

Personal stories

As the author unravels the layers in each film by going into the details of every character, storytelling style, music and script, she also fills us in with facts like when Aparna Sen started toying with the idea of directing a film, she had no clue about direction but as she says: “I saw vivid pictures in my mind and I was unafraid to ask questions. I was already dissatisfied with the roles I was playing.”

Although Kalpana Lajmi assisted Shyam Benegal for a long time it was her live-in relationship with the much older Bhupen Hazarika that led to the downfall in her career as a director, but she didn’t quit the relationship.

When Zoya Akhtar made her first film Luck By Chance, no one wanted to step into the role of a struggling actor till her brother Farhan Akhtar bailed her out. She even wove in this experience in the film script.

Gauri Shinde wrote and directed English Vinglish for her mother Vaishali Shinde who perpetually struggled with English. The author says that Gauri had actually confessed that the film was meant to be an apology to her mother who ran a pickle business from home.

Alankrita Srivastava started her career as trainee assistant director on Prakash Jha’s Gangaajal earning Rs 5,000 a month and she lived in a redeveloped slum because she had moved to Mumbai from Delhi.

The author says that Gauri had actually confessed that the film was meant to be an apology to her mother who ran a pickle business from home.

What I loved

As the author moves between the depiction of working women’s roles in films and the working styles, family background, inspiration and failures of the women behind the camera, what emerges is a narrative that’s rich, researched and real-life. The author has incorporated so many “Oh-really?” moments in the book by packing it with facts, figures and anecdotes that the interest in the book does not wane till the last page.

What is most thought-provoking is the conclusion that Soma A. Chatterji draws at the end of the book. I am not elaborating that here because the book should be read to understand her perspective.

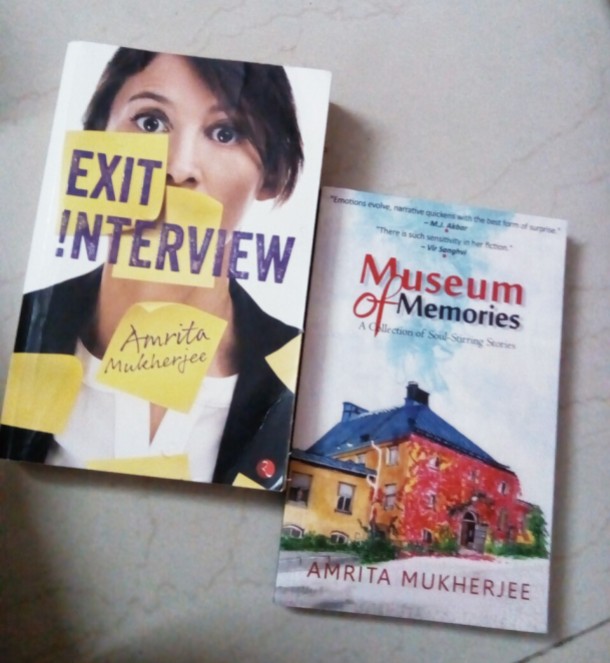

Book: Through the Lens, Brightly: Women in Cinema, Women at Work

Author: Shoma A.Chatterji

Publisher: Primus Books

Price: Rs 1495

*Photographs taken from the Internet

ShomaDi has always mesmerized me with her sea of knowledge and indepth research, bringing forth absolutely unheard and extremely interesting documents pertaining Indian Cinema and this book promises one more joyride❤! Thank you dear Amrita Di, for that fantastic review ❤🙏.

Totally agree with you. Shoma Di’s books are truly amazing.